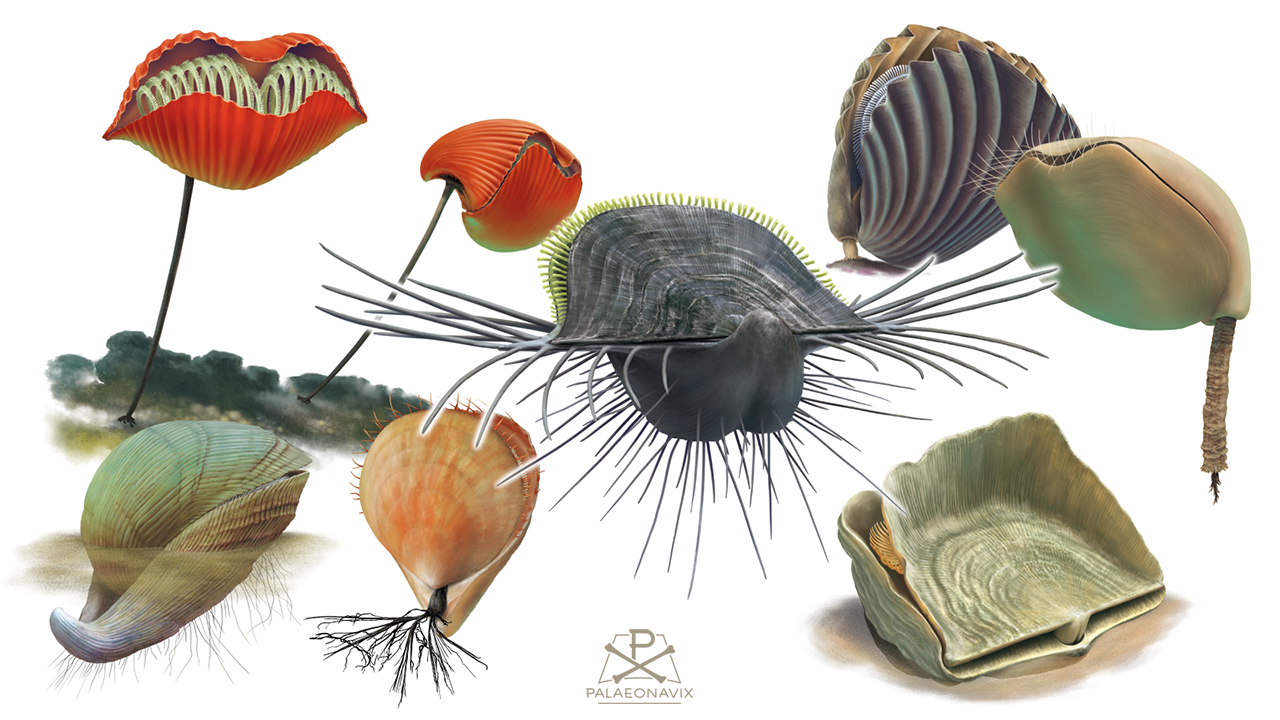

Marine invertebrates: rhynchonelliform brachiopods

At first glance, brachiopods have a universal structure: a coiled filter apparatus inside, a brachial valve at the top – i.e. not right and left as in bivalves – and a pedicle valve on the bottom, plus of course the pedicle as a muscular anchorage on hard surfaces. Most of today's rhynchonelliform brachiopods show this adhesive stalk. If one compares the exceptions with extraordinarily preserved fossils, a wider range becomes apparent. Some cling to objects as if they wanted to imitate byssate bivalves (Stringocephalus). Others apparently sent adhesive appendages through pores in their shells (Uncites). Thin stalks, which functioned as a tether, are documented by soft tissue preservation, while the curved shell of the floating brachiopod directed the water into the interior (Hysterolithes). Long spines made it possible to colonize soft ground without a stalk (Horridonia). A clear stalk hole therefore represents the primary condition (Rhynchonella, ribbed; Coenothyris, smooth). Where neither stalk nor spines are present, the shell lies flat, while the frill is intended to protect against inflowing sand grains (Leptaena).

digital painting, 2024

academic education, Tech.Univ. Bergakademie Freiberg